Swiss National Bank Investments in Fracking

Over 60,000 people demand: SNB, get out of fracking

The SNB manages a foreign exchange portfolio of approximately USD 849.9bn, of which 25% is in equities. The SNB Coalition (2023a) has analyzed this portfolio and published the complete list in the course of the SNB’s Annual General Meeting in 2023. This report refers to the companies on this list. The data is as of December 31, 2022. The SNB invests a total of around USD 16.1b in fossil fuel companies.

The aim of this report on the SNB’s investments in fracking companies is to show in more detail how large the central bank’s investment in these corporations is and how large the associated greenhouse gas emissions are. Fracking technology is put in the spotlight here because a majority of cantons reject it or have even banned it and because it has a particularly poor climate footprint. Furthermore, fracking is once again at the center of attention in global climate policy due to the Ukraine war.

In Brief

- Fracking systematically poisons waters and damages landscapes, leads to human rights violations in many places, and contributes substantially to global warming. According to the SNB’s own investment criteria, it should not invest in companies that engage in fracking.

- The SNB invests in 69 companies (as of the end of 2022) that produce oil and gas using fracking or transport oil and gas produced using fracking. The total investment amounts to nine billion US dollars.

- The SNB is responsible for greenhouse gas emissions due to fracking of around 7 MtCO2e through its investment shares. This is as much as the emissions of the entire Swiss agricultural sector.

- The planned expansion projects of fracking companies in which the SNB invests in would reduce the Swiss CO2 budget by another 81 MtCO2e. This is almost as much as Switzerland’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 and 2021.

- 14 cantons have positioned themselves against fracking. These cantons are home to 69 percent of the Swiss population and they own around three quarters of all SNB shares held by the cantons. There is strong opposition to fracking in urban and rural cantons, both in German-speaking and French-speaking Switzerland. Due to the broadly supported rejection of fracking by cantonal governments and the population, it can be considered a norm and value of Switzerland, which the SNB should also respect.

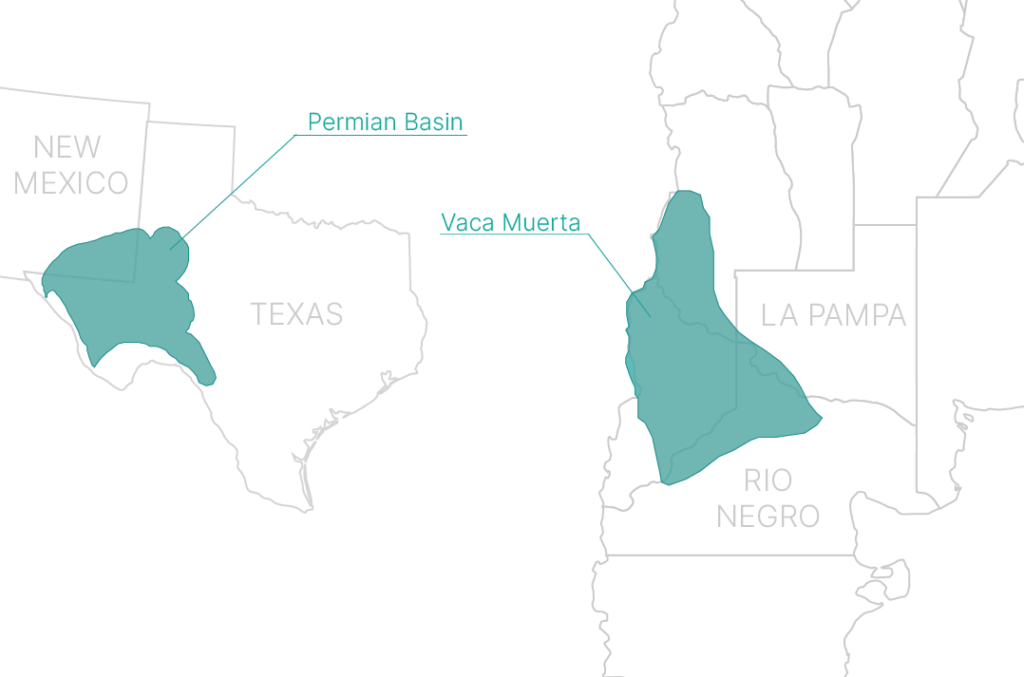

- The destruction of the environment and the health hazards due to fracking activities in the Permian Basin (USA) and Vaca Muerta (Argentina) described in the report impressively show why the SNB, as a shareholder of the fracking companies involved, must take measures.

- Currently, the SNB does not exercise its rights as a shareholder of environmentally destructive companies. It does not vote at general assemblies, nor does it submit motions. The SNB civil society coalition recommends a number of next steps to the SNB, the Federal Council and Parliament, as well as to the cantonal governments and cantonal banks which are listed in the chapter “Conclusions and Recommendations”. The SNB should exercise its shareholder rights, implement an escalation strategy in a transparent manner, and exclude environmentally destructive companies from its foreign exchange portfolio if the measures do not lead to an improvement.

- With the recommendations described, the SNB could pursue its existing investment guidelines more consistently, better ensure currency stability in the long term, respect Switzerland’s norms and values, and support the federal government’s sustainability goals, as well as the goals of the new Climate and Innovation Act (KIG). The law, which was clearly approved by the Swiss electorate, states that “financial flows must be directed towards low-emission development that is resilient to climate change”. As a state institution, the SNB is also obliged to make its contribution to reducing the climate impact of financial flows. This also includes their own investments.

Glossary

GOGEL: Global Oil & Gas Exit List

IEA: International Energy Agency

IMF: International Monetary Fund

Mboe: Million barrels of crude oil equivalents (energy unit)

SNB: Swiss National Bank

tCO2e: Tons of CO2 equivalents

GHG: Greenhouse gas emissions

Swiss Norms and Values

The SNB refers to the “norms and values of Switzerland” justifying its investment decisions. More specifically, the SNB writes the following in its investment guidelines:

«The SNB takes into account the fundamental norms and values of Switzerland within the framework of its investment policy. It does not invest in shares and bonds of companies whose products or production processes grossly violate widely accepted social values.

Schweizerische Nationalbank, 2022, S. 3

The SNB therefore does not acquire shares or bonds in companies that are involved in the production of internationally outlawed weapons, massively violate fundamental human rights or systematically cause serious environmental damage. The latter category also includes companies whose business model is based primarily on thermal coal mining.»

The “socially widely accepted values” are defined in more detail on the SNB’s website as follows:

«Outlawed weapons are defined as biological and chemical weapons, cluster munitions, and anti-personnel mines. In addition, the SNB also does not acquire shares in companies involved in the production of nuclear weapons for states that are not among the five legitimate nuclear powers as defined by the UN. Under the criterion ‘systematically serious environmental damage’, individual companies are excluded which, for example, systematically poison waters or landscapes or massively damage biodiversity in the course of their production »

Schweizerische Nationalbank, 2023b

Apart from these two passages, the SNB does not specify how it defines these norms and values or which body is charged with defining them. Nor is it noted at any point whether it uses certain empirical, or other objective or standardized criteria to do so.

In general, it can be noted that the SNB’s norms and values are very vaguely defined in the public’s perception and also lack some consistency, for example, the SNB continues to invest USD 322 million in Duke Energy, one of the largest coal companies in the world (SNB Coalition, 2023b). Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, investment in the company has almost tripled.

Fracking Violates SNB Investment Policy

With regard to fracking, it can be stated that this technology violates the standards and values defined by the SNB for several reasons at once.

Fracking technology has been used for decades as an unconventional method of extracting oil and gas. Since the 2010s, there has been a fracking boom, which revived with high oil and gas prices due to the Russian attack on Ukraine after a lull of several years.

The consequences of fracking for humans and their environment have been known for a long time. Due to the injection of chemicals in combination with water into the subsurface, there is a risk of groundwater contamination. In addition, contaminated water reenters the water cycle untreated through leaks or deliberate actions (NRDC, 2019). Furthermore, fracking leads to severe air pollution and regular earthquakes, which, among others, destroyed the foundations of entire cities in the Netherlands (Amin, 2015).

Especially since these risks are known to the fracking companies and they consciously accept them, one can speak of systematic environmental damage through the poisoning of water bodies, poisoning of the air and destruction of the landscape. According to its self-defined criteria, the SNB would thus be obliged to exclude fracking companies from its foreign exchange portfolio.

The SNB justified the exclusion of certain coal producers by stating that there was a strong consensus in Switzerland that the extraction of coal was not compatible with climate targets. The SNB is thus guided by broadly held views among the Swiss population. In public appearances, SNB representatives have repeatedly referred to past votes such as the CO2 Act to justify their investment decisions. In its report “The Swiss National Bank and Switzerland’s Sustainability Goals”, the Federal Council (2022) states that the SNB bases its assessment of Switzerland’s values on conventions and international agreements ratified by Switzerland, and on their transposition into Swiss legislation. Accordingly, the SNB includes current legislation in the assessment of its standards and values. This implies that the numerous cantonal legal bases against fracking must also be included in this assessment.

Cantonal Positions on Fracking

In parallel with the fracking boom in the USA, various companies also applied for licenses in Swiss cantons in the early 2010s to carry out test drilling for the potential extraction of natural gas using fracking. This announcement met with strong resistance from the population, parliaments and governments in many cantons. In the course of this, various cantons issued bans, moratoriums and positions against fracking in case of a company’s interest in the extraction of gas on the part of the industry. These came about through various means such as popular initiatives, parliamentary initiatives or the decision of cross-cantonal and cross-border interest groups in which the cantonal governments have a seat.

Currently1, six cantons have a ban on fracking, and three others have a moratorium. In addition, six cantons are members of the International Lake Constance Conference (IBK)2 which opposes fracking, and the Jura parliament wants to ban fracking in the future. This decision is supported by the Jura government and will be included in a draft of the new “Act on the Underground”. Eleven cantons have no position on fracking. The 14 cantons that reject fracking not only represent the majority of all cantons, but are also home to 69.10% of the Swiss population and own 27.33% of all SNB shares and almost certainly a majority of SNB shares held by the cantons.3

In most cantons that do not have a position on fracking, the extraction of gas or oil with the help of fracking has never been up for debate. So this cannot be taken as an endorsement of this technology. The canton of Basel-Stadt does not have a ban on fracking, but the clear approval of the Basel population for climate neutrality in 2030 or 2037, which is the most ambitious climate goal in Switzerland, can be interpreted as a general rejection of extraction technologies that are particularly harmful to the climate. Furthermore, the Basel-Stadt pension fund has been excluding fracking companies, among others, from its portfolio since 2021. Their explanation for this is (PKBS, 2021), “Shale oil and gas are also among the controversies, as their extraction requires large amounts of energy and water, as well as the use of chemicals that cause significant greenhouse gas emissions.”

Pressure from the local population, such as demonstrations or the launching of popular initiatives, was central to the rejection of fracking technology in most cantons. The rejection of fracking for the extraction of fossil fuels can be understood as part of Swiss norms and values due to the clear positioning of a majority of the cantons and the population with the help of various democratic means. It is also worth noting the rejection of fracking across the political spectrum, from the Greens to the SVP (Reimann, 2012).

SNB Investments in Fracking Companies

SNB invests at least USD 9.07 billion in fracking companies4, which corresponds to 4.27% of their equity investments. These funds are divided among a total of 69 companies. These include companies that use fracking to extract oil and gas, as well as those that transport it via pipelines.

This report calculates the share of production volume and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that can be allocated to SNB based on its investments. The detailed calculation of GHG emissions is attached in Appendix 4.

Emissions From Fracking

A total of 19.40 MtCO2e can be allocated to the SNB through the activities of the 68 fracking companies, which extract oil and gas through fracking, among other production methods.5 This includes GHG emissions from fracking and other extraction methods. This amount of emissions is considerable: All emissions from traffic and industry together in Switzerland are responsible for an amount of emissions equal to those from the SNB’s investments in fracking companies (Bundesamt für Umwelt, 2023).

The GHG emissions of these 68 fracking companies, which are due to oil and gas production by fracking and can be allocated to SNB, add up to 6.88 MtCO2e – a larger emission amount than that of the entire Swiss agriculture (Federal Office for the Environment, 2023).

Most oil and gas producers use various methods and technologies to extract fossil fuels, so the total emissions from companies that use fracking are higher than the emissions from fracking alone.

If SNB stopped investing in the 68 fracking companies, the resulting GHG emissions from gas and oil production for SNB would be reduced by more than four-fifths.

Development of SNB Investments in US Fracking Companies

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement (Q4 2015), the volume of SNB’s investments in the seven largest US fracking companies6 has increased by more than 254.40% by the end of 2022. The SNB’s equity portfolio grew by only 110.55% over the same period. The share of these US fracking companies in total equity volume was even higher in the fourth quarter of 2022 (2.18%) than it was after the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 (1.30%).

The SNB has been buying more shares in fracking companies again since 2021 and massively more since the outbreak of the Ukraine war. The reason for this seems to be the high demand for energy sources due to the reopening after the lockdowns and the shortage of Russian natural gas and oil. This made fracking production lucrative again. Since the SNB invests passively, it follows the general trend of the markets.

In the first half of the year, SNB sold shares in the fracking companies again. However, this change happened at a high level. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the volume of SNB’s investments in the listed fracking companies has always been higher than in each period since at least the second quarter of 2013.

Expansion Plans of Fracking Companies

Contrary to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) sharp warning that no new fossil sources should be developed to meet the 1.5 °C target (IEA, 2023), most fossil fuel corporations are planning to do just that.

The fracking companies in which the SNB invests plan to develop 34.06 GtCO2e of additional gas and oil wells, 17.08 GtCO2e of which will come from fracking alone. Proportionate to the investment volume, GHG emissions totaling 80.62 MtCO2e an be allocated to the SNB. The SNB’s emission share of the expansion in fracking could not be determined. If these fracking companies turn their plans into reality, this would result in an additional amount of emissions on top of the emissions from the already developed wells.

This means that the SNB invests in companies that are responsible for a total of 58.9% of all expansion projects in the fracking sector. It invests in 15 of the 20 companies with the largest imminent fracking expansion projects. In total, 63 of the 68 fracking companies in which SNB invests are planning to expand in the fracking sector over the next three years.

The expansion plans of the fossil corporations are thus in no way compatible with the Paris Agreement or with the 1.5 °C target.7

With its investments, the SNB is approving the structuring of a future economy that will continue to be massively dependent on fossil fuels. Many of these expansion projects will not be profitable for decades, so halting production early would result in massive write-offs.

Shareholder Behavior of the SNB

The Climate and Innovation Act (KIG), which was approved by a substantial majority of the Swiss electorate on June 18, 2023, states that “financial flows must be directed toward low-emission development that is resilient to climate change.”8 Art. 9 para. 1 of the KIG further states:

«The Confederation shall ensure that the Swiss financial center makes an effective contribution to low-emission development that is resilient to climate change. In particular, measures should be taken to reduce the climate impact of domestic and international financial flows.»

As a state institution, the SNB is also obliged to make its contribution to reducing the climate impact of financial flows. This also includes their own investments.

The SNB could influence the climate strategy of companies such as ExxonMobil through the enormous shares it holds. However, the SNB largely refrains from doing so because it only uses its voting rights with regard to good corporate governance at mid- and large-cap companies in Europe. The SNB reasons that “in the long term, good corporate governance helps companies” (Schweizerische Nationalbank, 2023d). By contrast, the SNB completely ignores environmental and sustainability risks when exercising its voting rights.

In the run-up to the SNB’s AGM in spring 2023, the SNB civil society coalition has submitted a motion to the AGM calling for the SNB to develop and implement an active shareholder engagement strategy. In view of the massive expansion plans of the aforementioned fracking companies, the SNB as a shareholder should demand science-based and time-bound transition plans from the companies that prevent expansion or further greenhouse gas emissions from fracking in line with the new Climate and Innovation Act. If a company does not have a credible transition plan or disregards it, the SNB should exit from that company.

Focus projects: Permian Basin (USA) and

Vaca Muerta (Argentina)

The extraction of oil and gas with the help of fracking not only has a devastating impact on global boiling, but also always means great suffering for the local population, often indigenous communities, and the environment. 26 companies in which the SNB invests are fracking in the regions with the world’s largest and second-largest reserves of shale gas: the Permian Basin (USA) and Vaca Muerta (Argentina).

Numerous reports from the local population, journalists, human rights and environmental organizations document impressively and consistently how extraction through fracking systematically poisons water bodies and landscapes, and massively damages biodiversity.

The SNB’s self-imposed exclusion criteria are clearly met by the known incidents in these two extraction areas. The SNB should therefore exclude the fracking companies in question from its portfolio on the basis of its existing criteria.

Permian Basin

Tens of thousands of oil and gas production facilities and pumps in the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico cover an area equivalent to the size of the cantons of Graubünden, Bern and Vaud combined. Most of this oil and gas is extracted with the help of fracking (Urgewald, 2023a). The Permian Basin is also the largest region in the United States where fracking is used.

With devastating consequences for the local population: the residents in the area are massively plagued by earthquakes caused by fracking. They inhale toxic fumes and have to flee their homes when thousands of liters of highly toxic wastewater laced with salt, toxic chemicals, oil, and radioactive minerals are released (Urgewald, 2023a). Ozone and smog pollution are also increasing due to fracking activities (Fann et al., 2018).

In the Permian Basin, not only are people and their environment being poisoned but the leakage rate of methane, a greenhouse gas that is particularly harmful to the climate, is 60% higher than in other extraction areas in the US (Urgewald, 2023b).

Pregnant individuals who are within five kilometers of active oil and gas production facilities have a 50% higher chance that their child will be born prematurely substantially increasing the risk of child illnesses (Cushing et al., 2020). The reason for this are so-called flares. Methane is ignited and toxic substances are emitted. Texas has the highest number of people living in close proximity to active oil and gas production facilities. Thus, they are particularly exposed to these hazards (D’Annunzio, 2022).

Numerous residents and organizations are resisting the destruction of their livelihoods by all means, legally and through direct action. In response, however, oil extraction or fracking was not banned, but their protest was gradually criminalized (Urgewald, 2023a).

There are 23 companies operating in the Permian Basin in which the SNB invests, including Chevron, ExxonMobil and Conocophillips. These are companies that directly produce oil and gas and use fracking (upstream), as well as companies that transport the produced oil and gas (midstream), for example through pipelines. The SNB invests a total of USD 5.3 bn in companies operating in the Permian Basin. A substantial part of the planned expansion by oil companies is happening in this region. ExxonMobil alone increased its production volume for 2022 by 25% compared to the previous year.

Vaca Muerta

In northern Patagonia (Argentina), oil and gas are extracted by using fracking, just like in the Permian Basin. There, too, people suffer from earthquakes and the poisoning of their environment (Urgewald, 2023b). Half a million liters of water contaminated by fracking flow into each one of the numerous wastewater ponds every day. In a lawsuit against the fracking plans, it is pointed out that a great danger emanates from the only poorly sealed basins. In addition, the practice violates local laws (Williams et al., 2019). Local people are also already reporting contamination of the water, which has led to health problems for them and their livestock. In addition, cases of fatal cancers, respiratory diseases, severe skin rashes, and decalcification of bones have been reported (Goñi, 2019).

Biodiversity also suffers greatly from fossil fuel extraction: nandus (ratites), capybaras, and maras (a subfamily of guinea pigs) have disappeared from Vaca Muerta (Livingstone, 2022).

The indigenous Mapuche community, which has lived in this region for centuries, suffers in particular from the fracking activities of fossil fuel companies. These were deprived of their land by the oil and gas companies and de facto expropriated. When the fracking plans became public in August 2013, the Argentine government suppressed Mapuche resistance with massive police violence. Since then, the Mapuche have repeatedly blocked the fracking process through blockades and protests.

A total of six companies, in which the SNB invested USD 4.9 bn, extract and transport oil and gas in Vaca Muerta, although even the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) has spoken out against this project (United Nations, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2018). In its report, the committee explicitly warns that consuming all of Vaca Muerta’s fossil fuels would greatly reduce the remaining global carbon budget. Since the publication of the report, a substantial part of this budget has already been used up.

IMF

But the SNB’s responsibility goes beyond its investment activities: the Argentinian government has high expectations of becoming less dependent on imports through increased fossil fuel production and even being able to export natural gas as LNG to reduce its huge debt. In 2018, the Argentinian government borrowed USD 57bn from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Vogt, 2022). The IMF repeatedly made clear that increased oil and gas production was necessary for debt repayment (Rijk & Kuepper, 2022). Until now, the Argentinian government has even had to subsidize the production of oil and gas.

Switzerland has a seat on the IMF Board of Governors. The Chairman of the SNB Governing Board is represented on this committee (Swiss National Bank, 2023c). Switzerland, which the SNB represents, can lobby for Argentina’s debt to be cancelled. This would take pressure off the Argentinian government to further fuel the climate crisis and destroy the local environment due to financial debt.

World Bank

In addition to the IMF, the World Bank also plays an important role in the extraction of oil and gas using fracking in Vaca Muerta. Specifically for fossil fuel extraction in Vaca Muerta, Pan American Energy received USD 400 million in 2015 from the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC). IFC is also investing USD 25 million in Medanito to extract fossil fuels in Vaca Muerta. It also mobilized an additional USD 25 million from private investors (Rijk & Kuepper, 2022). Switzerland leads a voting group at the World Bank and thus plays a central role in the allocation of funds in bodies such as the IFC. Although the current Swiss Minister of Economic Affairs serves as Governor of the constituency, the Chairman of the SNB Governing Board regularly attends the meetings of the constituency. Switzerland must oppose the financing of fracking in Vaca Muerta in the spirit of sustainable development and the 2030 Agenda, whose goals the Swiss government emphasizes in connection with its activities in the World Bank.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Fracking is an extremely dangerous and environmentally harmful technology. This has also been recognized by a majority of the cantons and the Swiss population. The numerous bans and moratoriums as well as the positioning against fracking show that the rejection of fracking is strongly rooted in the Swiss population and in current law. The rejection of fracking can therefore be seen as a norm and value of Switzerland in the same sense as the rejection of coal mining.

In light of the Climate and Innovation Act (KIG) recently adopted by a substantial majority, which explicitly requires climate action by the financial center and enshrines the Paris Agreement in law, the rejection of extraction methods that are particularly harmful to the climate and the environment, such as fracking, should also be accepted by the SNB as a norm and value of Switzerland.

Furthermore, fracking falls under the SNB’s formulated criteria, according to which investments in companies that poison water bodies and nature, and seriously violate human rights should be excluded. Numerous sources from the Permian Basin and Vaca Muerta show that in both areas water bodies, flora, fauna and the local population are systematically poisoned, despite warnings from governments and independent organizations. This leads to chronic diseases, deaths and premature births. The impact on the environment leads to a severe and persistent loss of species and biodiversity in general.

Argentina’s acute debt crisis, which was first delayed and now exacerbated by the covid pandemic, is leading to a sellout of the environment and the atmosphere. Through its strong position within multilateral bodies, particularly the IMF, Switzerland can work to ensure that Argentina’s debt is cancelled and Vaca Muerta is relieved of the ever-worsening environmental degradation and human rights crisis.

With this in mind, the SNB Coalition recommends the following further steps.

Swiss National Bank

Exercising Shareholder Rights

The SNB should assume take responsibility as co-owner of the companies in which it invests. To do so, it must exercise its shareholder rights, especially outside Europe, and adopt robust stewardship measures to ensure that companies in which the SNB invests align their business models with international climate and biodiversity goals and develop science-based and time-bound transition plans.

Implementation of an Escalation Strategy

Companies in which the SNB invests which cannot provide credible transition plans and continue to fuel the climate crisis, harm the environment, or violate human rights through their direct operations and supply chains should be subject to a robust and comprehensive escalation strategy. This strategy should initially include a vote against the management of the company, followed by divestment if sufficient progress is not made in a timely manner.

Create Transparency and set Goals

The SNB should disclose the detailed investment strategy for its foreign exchange portfolio by outlining all measures that are part of the escalation strategy (exposure, voting, divestment, etc.) as well as the detailed principles and rules for the selection of eligible assets to be included in the foreign exchange portfolio. In addition, the SNB should annually communicate science-based targets and measure and disclose progress in aligning its foreign exchange reserves with global climate and biodiversity goals.9

Federal Council and Parliament

Exercising the Supervisory Responsibility of the SNB

The Federal Council and Parliament should as part of their supervisory and accountability duties to the SNB critically compare and address the SNB’s foreign exchange portfolio and its negative environmental and social impacts with Switzerland’s commitment to international climate and biodiversity targets and the requirements of the new Climate and Innovation Act (KIG).10

Using Switzerland’s Voice in International Bodies

The Swiss authorities should advocate in multilateral organizations and bodies, especially the IMF and multilateral development banks, for debt relief for developing countries that are forced by “restructuring programs” or by servicing interest payments to extract fossil fuels using fracking or other technology that is harmful to people and nature.

Cantonal Governments and Cantonal Banks

Exercising Voting Rights

A majority of the cantons clearly position themselves against fracking. As collective majority owners, the cantons, cantonal banks and other cantonal or municipal institutions should advocate for an exclusion of companies that use fracking and other harmful technologies from the SNB’s foreign exchange portfolio.

Fussnoten

- As of July 1, 2023. ↩︎

- The canton of Appenzell-Innerrhoden is a member of the IBK, but has also banned fracking by law. ↩︎

- The proportion of shares is not known by all cantons. However, since the stock of shares roughly corresponds to the size of the population and the amount of shares is only unknown from small cantons, it can be assumed that the cantons with a negative stance on fracking hold a majority of all SNB shares in cantonal ownership. ↩︎

- Fracking companies are defined in this report as companies that produce (upstream) or transport (midstream) at least 2 Mboe of oil and gas using fracking technology. The Global Oil and Gas Exit List (GOGEL) of the NGO Urgewald (2022) serves as a source. ↩︎

- Kinder Morgan transports oil and gas extracted by fracking, but is not involved in the production itself. ↩︎

- The seven largest US fracking companies are those US-based companies in which SNB invests and which produced the largest amount of oil and gas through fracking in 2021. ↩︎

- The total GHG emissions resulting from the expansion of fracking company production would virtually halve Switzerland’s remaining CO2 budget of around 180 MtCO2 (see Appendix 3 for calculation). At the same time, the remaining budget would already be used up by mid-2026 and not by the end of 2028. Here it is assumed that all GHG emissions are in the form of CO2 emissions, since there is no budget for all GHGs. ↩︎

- Art. 1 lit. c KIG ↩︎

- For additional and detailed requirements, see https://unsere-snb.ch/forderungen/geldpolitik/ (in German and French only). ↩︎

- Art. 99 para. 2 of the Federal Constitution stipulates that the SNB must be managed in cooperation and supervision of the federal government. Pursuant to Art. 7 para. 2 NBA, the SNB must report annually to the Federal Assembly on the fulfillment of its tasks and explain its monetary policy to the responsible committees. Pursuant to para. 1, the annual report must be submitted to the Federal Council for approval prior to acceptance by the General Meeting. Para. 1 lit. c KIG stipulates that financial flows must be directed toward low-emission development that is resilient to climate change. ↩︎

Bibliography

Amin, L. (2015, October 10). Shell and Exxon’s €5bn problem: Gas drilling that sets off earthquakes and wrecks homes. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/oct/10/shell-exxon-gas-drilling-sets-off-earthquakes-wrecks-homes

Bundesamt für Statistik. (2022, October 6). Ständige Wohnbevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Kanton und Haushaltsgrösse—2010-2021 | Tabelle1.

Bundesamt für Statistik. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/de/23484614

Bundesamt für Umwelt. (2023). Treibhausgasinventar der Schweiz. https://www.bafu.admin.ch/bafu/de/home/themen/thema-klima/klima–daten–indikatoren-und-karten/daten–treibhausgasemissionen-der-schweiz/treibhausgasinventar.html

Bundesrat. (2022). Die Schweizerische Nationalbank und die

Nachhaltigkeitsziele der Schweiz. https://www.newsd.admin.ch/newsd/message/attachments/73603.pdf

Bureau van Dijk. (2023). Current Shareholders, Schweizerische Nationalbank [dataset]. Bureau van Dijk. https://orbis.bvdinfo.com/

Cushing, L. J., Vavra-Musser, K., Chau, K., Franklin, M., & Johnston, J. E. (2020). Flaring from Unconventional Oil and Gas Development and Birth Outcomes in the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas. Environmental Health Perspectives, 128(7), 077003. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP6394

D’Annunzio, F. (2022, June 1). Report: Texas leads the nation with most people living near active oil or gas wells. Dallas News. https://www.dallasnews.com/news/environment/2022/06/01/report-texas-leads-the-nation-with-most-people-living-near-active-oil-or-gas-well/

Direction Générale des Finances de l’Etat & Département des finances, des ressources humaines et des affaires extérieures (DF). (2023). Comptes de l’Etat 2022-Comptes individuels. https://www.ge.ch/document/31421/annexe/1

Fann, N., Baker, K. R., Chan, E. A. W., Eyth, A., Macpherson, A., Miller, E., & Snyder, J. (2018). Assessing Human Health PM 2.5 and Ozone Impacts from US Oil and Natural Gas Sector Emissions in 2025. Environmental Science & Technology, 52(15), 8095-8103. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02050

Goñi, U. (2019, October 14). Indigenous Mapuche pay high price for Argentina’s fracking dream. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/14/indigenous-mapuche-argentina-fracking-communities

IEA. (2023). Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. (2023). Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1. Ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

Lachat, D. (2018). Poussiéreuse loi sur les mines: Une mise à jourgente s’impose !

Livingstone, G. (2022, June 17). Standing firm against fracking. New Internationalist. https://newint.org/features/2022/04/04/fracked-earth

Lomax, A., & Savvaidis, A. (2019). Improving Absolute Earthquake Location in West Texas Using Probabilistic, Proxy Ground-Truth Station Corrections. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(11), 11447-11465. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB017727

NRDC. (2019, April 19). Fracking 101.https://www. nrdc.org/stories/fracking-101

PCAF. (2022). The Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard Part A: Financed Emissions.

PKBS. (2021, March 11). Nachhaltige Anlagepolitik: Ausschluss fossiler Energiesektor. PKBS. https://www.pkbs.ch/de/news/news-detail/nachhaltige-anlagepolitik-ausschluss-fossiler-energiesektor/

Reimann, L. (2012). 12.4262 | Kein Fracking. Zum Schutz des Bodensee-Trinkwassers sowie von Flora und Fauna | Geschäft | Das Schweizer Parlament. https://www.parlament.ch/de/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20124262

Rijk, G., & Kuepper, B. (2022). Vaca Muerta Basin: An Oil and Gas Trap. Profundo. https://350.org/press-release/worlds-second-largest-shale-gas-reserve-is-an-economic-bomb-shows-new-350-org-report/

Schweizerische Nationalbank. (2022). Richtlinien der Schweizerischen Nationalbank (SNB) für die Anlagepolitik.

Schweizerische Nationalbank. (2023a). Offizielle Währungsreserven und übrige Aktiven in Fremdwährungen [dataset] . https://data.snb.ch/de/topics/snb/cube/snbimfra

Schweizerische Nationalbank. (2023b). Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB)—Fragen und Antworten zur Verwaltung der Anlagen. https://www.snb.ch/de/ifor/public/qas/id/qas_assets#t29

Schweizerische Nationalbank. (2023c). Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB)—Internationaler Währungsfonds. https://www.snb.ch/de/iabout/internat/multilateral/id/internat_multilateral_imf#t2

Schweizerische Nationalbank. (2023d). Schweizerische Nationalbank (SNB)—Fragen und Antworten zur Verwaltung der Anlagen. https://www.snb.ch/de/ifor/public/qas/id/qas_assets#t29

SNB-Koalition. (2023a). Unsere Forschung. Unsere SNB. https://unsere-snb.ch/themen/problematische-investitionen/unsere-forschung/

SNB-Koalition. (2023b). Unsere SNB – Investitionen. Unsere SNB. https://unsere-snb.ch/themen/problematische-investitionen/

Thomson Reuters Eikon. (2023). CO2 Equivalent Emissions Indirect, Scope 1-3 [dataset].

Trede, A. (2013, March 19). 13.3108 | Fracking in der Schweiz | Geschäft | Das Schweizer Parlament. https://www.parlament.ch/de/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20133108

United Nations, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (2018). Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of Argentina. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2FC.12%2FARG%2FCO%2F4&Lang=en

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022.https://population. un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/MostUsed/

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2015, August 10). Greenhouse Gases Equivalencies Calculator-Calculations and References [Data and Tools]. https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gases-equivalencies-calculator-calculations-and-references

Urgewald. (2022). Global Oil and Gas Exit List (GOGEL). Gogel. https://gogel.org/

Urgewald. (2023a). Fracking in the Permian Basin. Gogel. https://gogel.org/fracking-permian-basin

Urgewald. (2023b). Vaca Muerta. Gogel. https://gogel.org/vaca-muerta

US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2023). EDGAR Company Search Results, Swiss National Bank [dataset]. https://www.sec.gov/edgar/browse/?CIK=1582202

Vogt, J. (2022, January 29). Argentiniens Deal mit dem IWF: „Hatten eine Schlinge um den Hals“. Die Tageszeitung: taz. https://taz.de/!5832459/

Williams, N., Costa, M., & Lamborn, K. (2019, October 14). How fracking is taking its toll on Argentina’s indigenous people – video explainer. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2019/oct/14/how-fracking-is-taking-its-toll-on-argentinas-indigenous-people-video